Additionally, the infraorbital foramen is determined by palpation by detecting a small depression at its location.

Intraoral method

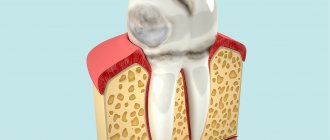

Location of the infraorbital foramen (target point of infraorbital anesthesia)

During this anesthesia, they also use permanent points located close to the infraorbital foramen and easily accessible to our eyes and hands. Such identifying points in this case are the lower orbital margin, infraorbitalis, pupil, some teeth, etc.

To determine the location of the infraorbital foramen, the following landmarks exist.

The infraorbital margin is divided in half and the location of the infraorbital foramen is determined 0.5 cm below its middle.

The location of the infraorbital foramen is also determined 0.5 cm below the place where the upper jaw and the zygomatic bone join to form the infraorbital margin, i.e. below the zygomatic-maxillary suture, sutura zygomaticoalveolaris. For most people, this place can be easily felt. This foramen can be identified by using a line drawn through the second premolar and through the mental foramen.

Moral and Cieszynski present the results of their measurements of the distances of the infraorbital foramen from the orbit and from the middle of the canine socket in children and adults.

| Authors | Children | Adults | ||

| from the middle of the canine socket | from the eye socket | from the middle of the canine socket | from the eye socket | |

| Morality | 20 mm | 5 mm | 34 mm | 7 mm |

| Cieszynski | 34 mm | 7 mm | 35.5 mm | 8.5 mm |

The table shows, firstly, that children have smaller distances (their jaw sizes are smaller); secondly, according to these authors, the distance of the infraorbital foramen from the orbit is approximately 0.5 cm; thirdly, from the socket edge in the canine area to the infraorbital foramen we have approximately 3.5 cm. The last number shows how far the needle needs to be inserted during an intraoral infraorbital conduction anesthetic injection.

In 1925, we examined the location of the infraorbital foramen on 75 turtles and 15 adult cadavers (see below) and found extreme variations in the distance from the infraorbital margin to the upper border of the infraorbital foramen from 4 to 8 mm.

| Distance of the infraorbital foramen from the infraorbital margin (in mm) | at both sides | on the right side | From the left side |

| 4 | 3 | _ | 2 |

| 5 | 35 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | 26 | _ | _ |

| 7 | 19 | 3 | _ |

| 8 | 2 | _ | _ |

From this table we see that the distance we are interested in is predominantly 5 mm, followed successively by distances of 6, 7 and 4 mm, and the rarest distance of 8 mm.

B.I. Gaukhman, D.A. Entin, in their studies on corpses and skulls of the distance from the infraorbital foramen to the lower edge of the orbit, found more significant amplitudes of fluctuations between the minimum and maximum sizes.

We determine the projection of the infraorbital foramen along a vertical line along a line passing through the second premolar (upper or lower) or through the mental foramen.

Technique for infraorbital anesthesia (injection site and needle direction)

The infraorbital foramen opens forward, downward and inward. The direction of the infraorbital canal is such that the extensions of the axes of both infraorbital canals intersect below the anterior nasal spine.

We insist that, in view of the origin of the anterior and middle superior alveolar nerves from the infraorbital nerve in the infraorbital canal itself and the groove of the same name, to obtain complete anesthesia from this conductive injection, it is not enough to bring the end of the needle only to the mouth of the infraorbital foramen and release the solution there, but you need to use a needle enter the most infraorbital canal 8-10 mm.

Other authors have found that by injecting an anesthetic fluid only near the infraorbital foramen, effective anesthesia can also be obtained. They suggest that to push the fluid into the canal, massage the soft tissue from the outside in the area of the infraorbital foramen.

We began to get very good results from infraorbital conduction anesthesia only when we began to insert a needle into the very infraorbital canal, and, since 1925, we have always performed infraorbital conduction anesthesia only intracanal. For only with this method of anesthesia can we achieve pain relief not only during normal tooth extraction, which can often be obtained, as mentioned above, with the help of correctly performed gingival infiltration anesthesia (the so-called plexual), but also during complex tooth extraction (such as gouging) and other surgical interventions on the anterior part of the upper jaw. The intracanal technique of infraorbital conduction anesthesia has an advantage over the extracanal one in that the analgesic effect with it is not only more pronounced, but also longer lasting, and also occurs faster, and also in the fact that only 0.4-0.5 ml of anesthetic solution. To obtain an analgesic effect from the extra-canal technique, not only in the area of the injected mucous membrane, but also in the bone, even just for the purpose of anesthetizing a normal tooth extraction, 4-5 ml of solution should be injected, since only as a result of abundant saturation of the external soft tissues part of the solution slightly seeps into the bone. With the intracanal route of infraorbital conduction anesthesia, not only the mucous membrane, periosteum, outer wall of the alveolar process, teeth, the corresponding section of the mucous membrane of the maxillary cavity, but partly the palatal wall of the alveolar process are anesthetized in its zone.

It should also be noted that with full infraorbital conduction anesthesia, i.e., anesthesia performed intracanal, often, if we move the needle a little deeper and inject an anesthetic solution into the infraorbital canal, we can anesthetize a significant area of the posterior segment of the upper jaw. In these cases, the anesthetic solution, injected deeply and under a certain pressure into the canal, seeps along the infraorbital nerve in the infraorbital canal and the groove of the same name towards the back, also anesthetizing the posterior segment of this nerve. This circumstance is important when, for one reason or another, it is impossible to perform either a tubercular or pterygopalatine anesthetic injection, and it is necessary to operate not only in the zone of infraorbital conduction anesthesia, but also much more proximally.

However, if it is necessary to perform infraorbital conduction anesthesia intracanal, this does not mean that it is permissible to injure the anesthetized nerves with a needle moving close to them. You need to learn how to work this way and monitor the advancement of the injection needle deep into the infraorbital canal so that even if it is necessary to deviate from the rule of perineural administration of an anesthetic injection, it still does not cause complications. It is necessary that the end of the needle is not too long and not too flatly beveled and, what is especially important, during this conductive injection, during the entire time the needle is advanced, release an anesthetic solution in small portions, which moisturizes the entire path of the needle and pushes aside the vessels and nerves located in infraorbital canal. The needle must be advanced very slowly into the canal.

To enter the infraorbital canal with a needle, the syringe must be directed back, up and out. This direction of the needle can be achieved with the extraoral method of this conductive anesthetic injection (when the injection site is outside the oral cavity).

M. F. Datsenko discovered a double infraorbital and double mental foramen during the dissection of corpses.

The author examined the skulls located in the anatomical museum of the Moscow Dental Institute, and out of 78 skulls he discovered a double infraorbital foramen in one case.

In order to identify the frequency of anomalies in the number of the infraorbital foramen, as well as the anatomical features of this foramen in these cases, we, together with our employee Assoc. In 1952, S.I. Bukh-Chechik examined part of the skulls stored in the anatomical museum of the Department of Normal Anatomy of the Kyiv Medical Institute. As a result of examining 250 skulls, we obtained the following data.

An abnormality in the number of the infraorbital foramen was noted in 20 turtles. In 5 skulls, the double infraorbital foramen was located on both sides (on both upper jaws). A triple infraorbital foramen was found on two skulls: in one case on the right side, and in the other on the left. On the remaining 13 turtles, a double infraorbital foramen was observed on one side: 8 times on the left and 5 times on the right.

Datsenko, on the basis of the anomaly he discovered in the number of the infraorbital foramen, objects to the advisability of the intracanal technique of infraorbital conduction anesthesia due to the alleged difficulty of performing it with this anomaly.

We cannot agree with this objection for the following reasons.

A doubled, and even more so a tripled, infraorbital foramen is rare. In addition, and this is the main motive, as we have seen in our examinations of these skulls, in the presence of a double or triple infraorbital foramen, one of them, the so-called main foramen, always has the usual position and the usual size, and the additional foramen, as a rule, is very small in size and occupies an unusual place, most often lateral to the main opening. Thus, if there is an anomaly in the number of the infraorbital foramen, there are no difficulties for the intracanal technique of infraorbital conduction anesthesia.

When should infraorbital anesthesia not be used?

Anesthesia of the infraorbital nerve has a number of contraindications. This procedure cannot be performed in the following cases:

- If the patient is allergic to anesthetics used for pain relief.

- In case of abnormalities in tissue anatomy as a result of trauma, due to which the correct administration of an anesthetic injection becomes impossible.

- For long duration surgical procedures exceeding three hours.

- If the patient has mental disorders.

- If the patient has heart disease, or if he has recently had a heart attack.

- During pregnancy. In rare cases, articaine drugs can be used.

Intraoral method of infraorbital anesthesia

With the intraoral method of infraorbital conduction anesthesia, the boundaries of the vestibule of the mouth, vestibulum oris, prevent unhindered penetration of the needle into the very infraorbital canal. The entrance (for the needle) opening of the canal lies on a vertical line drawn through the second premolar. Previously, the injection was made in this area (i.e., above the upper second premolar). But the direction of the needle is very different from the direction of the channel:

The needle moves up and back, and the channel goes up, back and out (laterally). To eliminate this discrepancy as much as possible, and also to avoid steep transitions, the following is suggested:

1) the injection site should be between the upper central and lateral incisors of the corresponding side;

2) the lip needs to be raised more;

3) the injection should be done higher - at the arch of the vestibule, förnix vestibuli, and not too close to the alveolar process, but away from it - in the soft parts of the lip (about one centimeter from the anterior surface of the alveolar process).

This ensures that the needle directed to the infraorbital foramen will go moderately steeply upward and backward and at the same time outward. With this direction, the needle can relatively easily enter the canal by 8-10 mm.

Other authors make an injection above the canine. But they, as has already been said, do not seek to penetrate the canal with a needle, since for their purposes it is enough that the end of the needle only comes close to the infraorbital foramen, and they succeeded in this without difficulty even at such an injection site.

For many years we have been performing intraoral infraorbital conduction anesthesia with an injection at the level of the apexes of the teeth between the central and lateral incisors, and we almost always manage to enter the desired distance into the canal. Until 1925, we gave injections above the premolars, but did not achieve the desired success. We have often noticed that a more medial injection site produces better results, since it is likely to achieve closer contact with the infraorbital foramen.

The intraoral method of infraorbital conduction anesthesia is carried out in various ways.

Sicher and other authors recommend fixing the location of the target point of anesthesia - the infraorbital foramen and pulling the upper lip up and forward on the right side with the fingers of the left hand, and with the left, with the fingers of the right hand, and perform the injection on the left with the left hand. With this method, the end of the index finger lies firmly on the infraorbital foramen, and the upper lip is pulled up and forward with the thumb.

We recommend that with this anesthesia, as with all other conduction anesthesia in the maxillofacial area, fixing the location of the target point (and with this anesthesia, also retracting the upper lip should be done with the fingers of the left hand on both the right and left sides of the patient, and the injection swipe on both sides with your right hand.

In this case, not the index, but the middle finger of the left hand is placed on the skin of the face in the projection of the infraorbital foramen, the upper lip of the corresponding side is pulled up and forward with the index and thumb of the left hand, and the injection is carried out on both the right and left with the right hand. A long (4.5-5 cm) needle is inserted into the tissue at the level between the roots of the upper central and lateral incisors in the transitional fold so that the injection occurs in the soft tissues almost 1 cm away from the bone. Then turn the needle towards the infraorbital foramen, advance it slowly to the bone area, on which the third finger fixing the target point is held, and there a small amount of anesthetic solution (about 0.5 ml) is released (under the control of the finger) to be able to carry out further manipulations are painless. The end of the needle, while constantly palpating the anesthetized bone space, slowly slides towards the target point and enters the infraorbital foramen. The penetration of the needle into the infraorbital foramen and canal is clearly felt by both the doctor and the patient due to the fact that the needle comes into contact with the trunk of the infraorbital nerve. Continuing to release the anesthetic liquid little by little, advance the needle 8-10 mm deep into the canal and then inject 0.5 ml of solution. After 2-3 minutes (often instantly), anesthesia occurs.

If there are inflammatory foci in the area of the upper incisors, infraorbital conduction anesthesia is performed extraorally.

Technique for intraoral infraorbital anesthesia between the canine and the first premolar:

1. Using the index finger of the left hand, fix the projection of the infraorbital foramen to the bone; with the thumb, pull the upper lip up to the index finger (Fig. 75, B). 1. The needle is inserted 5-7 mm above the transitional fold between the canine and the first premolar, moved back, up and in the middle so that it approaches the infraorbital foramen (Fig. 75, B).

Rice. 75. Stages of performing intraoral infraorbital anesthesia for an injection between the canine and the first premolar : A - the path of advancement of the needle during intraoral infraorbital anesthesia between the canine and the first premolar, the zone of dental anesthesia for infraorbital anesthesia is indicated (diagram); B: Stage I - soft tissues are fixed with the index finger and thumb; B: Stage II - the needle is inserted 5-7 mm above the transitional fold between the canine and the first premolar, advanced to the mouth of the infraorbital foramen

The following steps are similar to the above intraoral infraorbital anesthesia method. With this anesthesia, the solution is injected into the mouth of the infraorbital foramen, which prevents injury to the neurovascular bundle. It should be noted that when using a strong anesthetic, there is no need to administer an anesthetic solution intracanal.

Extraoral method of infraorbital anesthesia

We palpate and fix the surgical field with the left hand when injecting on both the right and left sides and always initiate with the right hand. Our recommended technique eliminates crossing the arms.

When injecting on the right side, place the index finger on the infraorbital edge (on its lateral part) so that the tip of the finger falls in the middle of the said edge and so that the radial edge of the finger marks the location of the infraorbital foramen. We place the thumb on the patient’s cheek so that it simultaneously stretches the soft tissues, which facilitates their puncture, and fixes the injection site, which should be slightly medial and below the infraorbital foramen.

Since the infraorbital foramen is open forward, downward and inward, and the infraorbital canal has the same direction, we must give the needle a direction from front to back, bottom to top, and from inside to outside.

We inject the needle directly to the bone, often at this injection site and in this direction of the needle we immediately get into the infraorbital canal. This can be recognized by the fact that you can easily move the needle 8-10 mm deep. If the needle does not fall into the hole, but onto the bone, we immediately release a little anesthetic solution, since it is easier to slide along the moistened and anesthetized bone area and get into the hole.

When injecting on the left side, we place the index finger of the left hand on the lower orbital edge, but here on its medial half. Place your thumb on the side wall of the nose. The end of the index finger here also fixes the location of the infraorbital foramen, and the end of the thumb marks the injection site. Then we proceed in the same way as when injecting on the right side.

Since 1928, we have been performing infraorbital conduction anesthesia primarily using the extraoral method. The extraoral method of infraorbital conduction anesthetic injection is preferred because it is technically easier and extraoral injections are more sterile.

Complications of infraorbital anesthesia

1. Injury to the vessels located in the area of needle advancement. With this anesthetic injection, you can injure, firstly, the angular artery, the external maxillary artery and the anterior facial vein, art. angularis, art. maxillaris externa et vena facialis anterior (these vessels are crossed by the course of the needle). But we know that the vessels move to the side when the needle approaches them (this creates difficulties with intravenous injections), especially when the anesthetic solution is continuously released. Secondly, the infraorbital artery and accompanying veins can be injured here. Injury to these vessels occurs, according to some authors, in 2-3% of cases. In our practice, vascular injury with this anesthetic injection is a rarer occurrence.

The prevention of vascular injury and other complications that may arise from it will be discussed below.

2. The needle gets into the eye socket. To avoid this complication, you should not advance the needle into the depths of the infraorbital canal to a distance of more than 8-10 mm. If it happens that the end of the needle enters through the infraorbital canal into the orbit, for example, when the needle is advanced deeper into the canal or if its length is insignificant, then transient double vision and some swelling of the soft tissues surrounding the eyes can only occur; there are no more serious consequences. Only with extremely rough and deep advancement of the needle through the infraorbital canal into the orbit can the eyeball be injured.

3. Paresis of the muscular nerves of the eye (most often mi inferiores nervi oculomotorii). This complication occurs when an anesthetic solution gets into the eye socket. It is accompanied by transient double vision. But, as we said, the needle entering the orbit through the upper wall of the infraorbital canal when entering the canal no more than 10 mm is almost completely excluded.

4. If the solution enters the orbit through the lower orbital margin, it is revealed by swelling of the lower eyelid. There are no serious consequences from this.

5. Pallor of the facial skin at the beginning of the injection can also occur with this anesthesia, but here this phenomenon is not surprising, since the injection is performed near the vessels that directly supply the facial skin.

Area of spread of anesthesia. Typically, after infraorbital conduction anesthesia, the area from the middle of the upper central incisor to the middle of the upper second premolar on the labio-buccal side, including the corresponding area of the upper jaw and teeth, is anesthetized. Medial and lateral to this area, anesthesia does not occur due to anastomoses from the anterior superior alveolar nerves of the opposite side (medially) and from the posterior superior alveolar nerves of the same side (laterally).

Sometimes (although very rarely) the teeth are anesthetized only up to the canine (both incisors and the canine). This can be explained by the fact that the solution did not reach the nerve behind the infraorbital canal, where the middle superior alveolar nerves, which play a major role in nerve supply to the upper premolars, are almost always separated, which usually happens with extracanal infraorbital conduction anesthesia, or by the fact that the middle superior alveolar nerves arise outside the infraorbital canal and the groove of the same name (before the infraorbital nerve enters the orbit through the inferior orbital fissure), or, finally, by the fact that the upper premolars in this case are innervated by branches from the posterior superior alveolar nerves. In the mucous membrane on the palatal side, anesthesia does not occur, since this is the area innervated by the nasopalatine and anterior palatine nerves.

It must be added that, in addition to anesthesia of the upper jaw within the mentioned boundaries, with infraorbital conduction anesthesia we also achieve anesthesia of the lower eyelid (except for the lateral part), the side of the nose (except for the back and tip), half of the upper lip and the front part of the cheek. This is explained by the fact that after injection into the infraorbital canal, not only the area of branching of the anterior and middle superior alveolar nerves is anesthetized, but also the area of branching of the infraorbital nerve, protruding through the infraorbital foramen onto the anterior surface of the upper jaw (lesser pes anserine).

The intraoral technique of infraorbital conduction anesthesia is less successful than the extraoral one. This is due not only to the possibility of introducing an oral infection during the intraoral technique of this anesthesia, which is especially dangerous in a heavily infected oral cavity, but also to the fact that the technique of intraoral infraorbital conduction anesthesia is much more complicated than extraoral one. With an intraoral infraorbital anesthetic injection, it is necessary to deviate from the most important rule of conduction anesthesia on the jaws, which requires that the needle advanced into the depths of the perimaxillary soft tissues be kept close to the bone at all times. It should be emphasized that the need to insert a needle into the very infraorbital canal makes the intraoral technique of this anesthesia even more complex and reduces the likelihood of success.

The extraoral technique of infraorbital conduction anesthesia is easier and, therefore, more accessible.

Infraorbital conduction anesthesia, as indicated at the beginning, plays an important role in anesthesia of the upper jaw. When carried out intracanal, it completely anesthetizes almost two-thirds of the upper jaw. It can and should take pride of place among the methods of conduction anesthesia of the dental system. It can and should play almost the same role for anesthesia of the upper jaw as mandibular conduction anesthesia plays for conduction anesthesia of the lower jaw.

In case of failure, when we were unable to get into the infraorbital foramen and, consequently, into the infraorbital canal (this happened during the first time we developed this anesthesia), we released the anesthetic solution outside the infraorbital canal. This was sometimes relatively sufficient to anesthetize minor interventions (routine tooth extraction, etc.), and in cases where a significant and very painful intervention was to be performed, we used central conduction anesthesia at the round hole (about anesthesia at the round hole and the ways of its implementation, see . Further). Failures, i.e. cases of failure to enter the infraorbital canal, even with the extraoral technique of infraorbital conduction anesthesia are relatively common.

Wanting to reduce the percentage of such failures and bring it to a minimum even among inexperienced doctors, we set ourselves the task of modifying the technique of extraoral infraorbital conduction anesthesia. Having studied a large number of skulls and corpses for this purpose, we were convinced that the infraorbital foramen does not always open exactly obliquely downward and inward. In a significant percentage of cases, this hole is directed either only inward, or, more often, almost completely downward.

Considering the existence of these options for the direction of the infraorbital foramen, we recommend the following technique for performing extraoral infraorbital conduction anesthesia.

From the usual injection site, the needle is first directed obliquely, from below and from the inside, up and out. If it does not hit the infraorbital foramen, this way they switch to the direction from bottom to top, for which they slightly extend the needle and again, after moving the soft tissue at the injection site, slightly move it outward in the indicated direction (from bottom to top). In case of failure, take the direction from the inside to the outside, for which they again slightly extend the needle, lift the tissue at the injection site slightly upward, then direct the needle from the inside to the outside and enter the infraorbital foramen.

Our research, based on the study of over a hundred skulls for this purpose, has established the following regarding the options for the direction of the infraorbital foramen. In approximately 60% of cases, the orifice is directed obliquely downward and inward, in 25% - mainly downward and only slightly inward, and in 15% - mainly inward.

In the technique of extraoral infraorbital anesthesia, the depth of the canine fossa should also be taken into account. With a very deep canine fossa, getting the end of the needle stuck in it can prevent successful entry into the mouth of the infraorbital foramen. To avoid this, the injection begins closer to the projection site of the infraorbital foramen and, thus, has the opportunity to reach the area of the bone located above the canine fossa. With such an injection site, you can almost always easily get into the infraorbital foramen, even with a very deep canine fossa.

Complications of palatal anesthesia

- Paresis of the soft palate. If the anesthetic solution gets into this area, temporary paresis of the soft palate may occur. The patient in this case complains of a feeling of some kind of plaque on the soft palate, the presence of a foreign body in this place, as with a sore throat. Paresis of the soft palate in some patients causes coughing and vomiting, which sometimes ends in vomiting when the stomach is full. If you bring the needle close to the bone, the anesthetic solution enters the less loose tissue and cannot spread back so easily. It should also be noted that paresis of the soft palate can occur not only in cases where the needle is not brought to the bone, but also under the following circumstances: firstly, when the injection site or the direction of the needle is taken incorrectly (more medially and backward); secondly, when too much solution is released during this anesthesia. It must be remembered that the limit here is 1/2 ml. Usually they limit themselves to an even smaller amount of anesthetic solution.

Paresis of the soft palate due to the entry of an anesthetic solution into the motor nerves of his muscles does not pose anything dangerous, since it passes quite quickly without any trace.To eliminate these unpleasant sensations and prevent vomiting, the patient is given a little water to drink. Sometimes these unpleasant sensations go away after several deep breaths of fresh air.

- Vascular injury. This complication occurs here quite often, but due to the absence of any more or less large vascular branches in this area, it is not of particular importance. Vascular injury occurs here more often than with conductive anesthetic injections in other places, because near the greater palatine foramen there is a dense network of vessels, one of which can easily be penetrated by a needle. A vessel injury is recognized by slight bleeding from the injection site after removal of the needle. This bleeding stops quite quickly on its own or is stopped by pressing the injection site with a gauze pad.

- The appearance of ischemic (blanched) areas of facial skin. Sometimes the anesthetic solution during palatal conduction anesthesia through the pterygopalatine canal enters the pterygopalatine fossa and acts on one of the vessels lying in it, which, as is known, are connected with the vessels of the facial skin; As a result, temporary ischemia appears over a fairly large area of the face.

An anesthetic solution can affect the vessels of the pterygopalatine fossa through the pterygopalatine canal not only when it penetrates into the bloodstream due to injury to a blood or lymphatic palatine vessel. The anesthetic solution can leak between these vessels up to the pterygopalatine fossa without stopping them. The possibility of penetration of the anesthetic solution through the pterygopalatine canal was confirmed by our experiments on corpses using the injection of colored gelatin at the greater palatine foramen. After opening and dissecting the pterygopalatine canal, we found threads of colored gelatin in the canal itself between the vessels and nerves.Adrenaline contained in the anesthetic solution, penetrating one way or another into the pterygopalatine fossa, can cause contraction of a large vessel that gives branches to the skin of the face. Hence the ischemia of the facial skin area. By the contours and location of the area of ischemia on the face, one can judge which vessel was exposed to adrenaline.

Ischemia of areas of the facial skin occurs either immediately after injection and even at the beginning of it, when it is associated with vascular spasm due to contact of the needle with the vessel, or after 1-2 minutes after injection, when it occurs as a result of the vasoconstrictor effect of the adrenaline contained in the anesthetic solution .

Ischemia in certain areas of the skin of the face does not last long, especially when it is associated with a spasm of the vessel from the touch of a needle, and most often completely disappears after approximately ½ - ¾ hours. In rare cases, blanching of skin areas remains for 2-3 hours.

The sensitivity of pale areas of skin decreases very slightly. Most often, ischemia with this anesthesia covers the corner of the mouth, half of the upper lip and nose, the front of the cheek, the inner corner of the eye and the infraorbital region on the corresponding side. More extensive areas of facial skin ischemia are also observed, including the supraorbital region. In the first case, we are apparently dealing with the entry of an anesthetic solution into a vessel when it is wounded, and in the second, with the leakage of the solution between the walls of the vessels without wounding them. It must be assumed that the anesthetic solution, seeping between the vessels without injuring any of them, can narrow several vessels, affecting their walls, and as a result cause ischemia of a larger area of facial skin. However, even with infiltration anesthesia on the palate, even in the area of premolars and canines, ischemia is possible in large areas of the facial skin.

It should only be added that, since blanching of an area of facial skin is usually caused by injury to a vessel and the entry of an anesthetic solution into it, sometimes when post-injection ischemia appears in a particular area of facial skin, other complications are observed (the harmful effect of the anesthetic solution on the body and the lack of anesthesia). These complications will be discussed in detail below.

Let us note, by the way, that with this injection there is no need not only to enter the pterygopalatine canal with a needle, but even to go very close to the opening itself: we do not need to interrupt the conduction of the nerve in the part lying in the canal, but it is enough to wash the nerve with the solution immediately upon exit it from the greater palatine foramen. To relieve pain from surgical interventions in the maxillofacial area, as already mentioned, we use the perineural method of conduction anesthesia; The solution reaches the nerve by diffusion. Knowing this, when injecting at the greater palatine foramen, we try to release the solution in front of the opening. Anesthesia of the anterior palatine nerve will also occur, but the danger of paresis of the soft palate and injury to the vessel is reduced (the latter is explained by the fact that the closer to the front, the smaller the vessels and are less likely to be injured).

Orbital route of infraorbital anesthesia

We have already emphasized that for successful infraorbital conduction anesthesia to obtain complete anesthesia not only of the outer mucous membrane and periosteum in the area of the five upper teeth, from the central incisor to the second premolar, but also of these teeth themselves, the bone walls of the upper jaw and the maxillary mucosa cavity in the corresponding area, this anesthesia should be performed intracanal, with the end of the needle entering the infraorbital canal by 8-10 mm. For extracanal infraorbital anesthesia, with the tip of the needle and anesthetic solution brought only to the infraorbital foramen, as a rule, well anesthetizes only the terminal branches of the infraorbital nerve emerging from the infraorbital foramen (the so-called lesser pes anserine), which innervate only the outer one in the zone of this anesthesia on the upper jaw mucous membrane and periosteum. The anterior and middle superior alveolar nerves, which extend from the infraorbital nerve in the infraorbital canal itself and the groove of the same name and innervate the indicated five teeth, the area of the upper jaw and the mucous membrane of the maxillary sinus within the specified limits, usually remain painless during extracanal anesthesia.

As our experience shows, only intracanal infraorbital conduction anesthesia well anesthetizes the tissues surrounding the tooth, the pulp and hard tissues of the tooth, which makes it possible not only to painlessly remove the tooth, but also to completely painlessly dissect the hard tissues of the tooth, as well as amputate and extirpate the pulp.

At the same time, it is not always easy when carrying out infraorbital conduction anesthesia (extraoral and especially intraoral) to get into the infraorbital foramen, from there go deeper into the canal of the same name and wash the infraorbital nerve with a solution in the canal itself, especially in the groove, in those places where it departs from the nerve its anterior and middle superior alveolar branches. This circumstance is associated not only with the different diameters of the infraorbital foramen and the canal of the same name in different people, but primarily with the fact that in different people the location of the infraorbital foramen and the direction of its mouth vary significantly.

Naturally, it is easy to perform conduction anesthesia with complete success in the case when the nerve to be anesthetized is accessible for washing away with an anesthetic liquid either before it enters the corresponding opening and canal, such as the posterior superior alveolar nerves and the inferior alveolar nerve, or after its exit from the foramen, as the anterior palatine nerve, as well as the maxillary and mandibular nerves.

We were faced with the question of whether it is possible to carry out infraorbital conduction anesthesia extracanal and still obtain complete anesthesia of both the terminal branches of the infraorbital nerve and those extending from it in the infraorbital canal and the groove of the same name of the anterior and middle superior alveolar nerves, innervating the area of the upper jaw ranging from the central incisor to the second premolar along with these teeth. In other words, we were faced with a question: is there a way of infraorbital conduction anesthesia in which the needle and anesthetic solution would be brought to an accessible part of the infraorbital nerve before the departure of the branches of interest to us, bypassing the hole and canal?

At the beginning of 1954, we proposed this path. It lies on the side of the eye socket.

It is known that on the lower wall of the orbit, close to the infraorbital margin, approximately 1 cm from it, the infraorbital groove runs sagittally, in which the infraorbital nerve lies freely, without bone covering, before its entry into the infraorbital canal, located at the level of the middle of the infraorbital margin and opening on the facial surface of the upper jaw with an infraorbital foramen.

Anesthesia at the greater palatine foramen - palatal (palatal) conduction anesthesia

The upper jaw and the soft tissues covering it receive nerves from two sources. One source is the infraorbital nerve with all its branches - the posterior, middle and anterior superior alveolar nerves - and the infraorbital nerve (part of the nerve of the same name that projects through the infraorbital foramen onto the facial surface of the maxilla). The other is the main palatine ganglion with all its branches, namely: the superior posterior nasal nerves (among them the nasopalatine nerve), the inferior posterior nasal and palatine nerves (anterior palatine and posterior palatine). Due to the first source, as we have already seen, the outer part of the upper jaw (labio-buccal) with teeth and soft tissues covering the jaw on the vestibular side, as well as the corresponding segment of the mucous membrane of the maxillary cavity and the palatal bone wall of the jaw are innervated; due to the second source - the mucous membrane and periosteum from the palate and nasal cavity.

The anterior palatine nerve, which is a branch of the main palatine ganglion, passes along with other palatine nerves through the pterygopalatine canal and then exits separately through the greater palatine foramen to the oral surface of the palate, where its terminal branches extend to the mucous membrane of the hard and soft palate and to palatal side of the gums.